Says Strecker: Several years ago I met Rudy Fecteau and began an ongoing conversation with him on many subjects -with one overlapping onto another or implying another or confiscating another. Some of these are subjects discussed in the interview that now follows. Think Leonardo painting the Mona Lisa and also doing the plans for a flying machine and proceeding to other areas of study, and then let us begin:

James Strecker: Okay, to begin, what does an archaeobotanist do and why do you, yourself do it? What got you interested in archaeobotany in the first place? Which takes the lead – the archaeology or the botany?

Rudy Fecteau: An archaeobotanist analyzes carbonized plant material from archaeological sites. This includes pre-contact, contact and Euro-Canadian sites. I have also identified palaeo-environmental material from the northern climes of Western Canada for a palaeo-environmentalist. The reason I am in the position to study the past in a different way is fortuitous. As an unemployed archaeologist in the mid 1970’s, I obtained employment as a typist for the botany department at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. I was told that the job would last about four weeks but I completed it in three days (I could type!). Dr. McAndrews then had me work on sorting through and identifying charred wood and seeds from a late 16th century Huron/Wendat site near Woodbridge, Ontario interestingly called the Seed site. That was forty years ago and, even though I’ve had other jobs in the meantime, I have continued to do this work for the archaeology community during evenings, holidays and vacation time. Since I spent much of my time in archaeology focusing on plant material, I started doing less field work and more lab work. As I aged and damaged my knees, it became much easier to do the lab work than the field work.

It is during my retirement years that I have been able to fully establish myself as an archaeobotanist with all its attendant responsibilities of analysis, report writing, article writing and academic and public presentations. And I can get paid!

JS: You’re an intriguing combination of interests. You also paint, you write, you photograph, you cook, you create means of presentation, you’re an obsessive teacher, and who knows what else? Please explain these and other activities you choose to have in your life and how they work together.

RF: The basic point is that, in spite of being retired for eight years, I don’t know what I want to be when I grow up. Over the years I have sketched, drawn cartoons, and made illustrations of plants, etc. A decade or more ago I took the first of several watercolour courses at DVSA. A gift of a digital SLR camera led me to take some photography courses there as well. During another period of unemployment, I spent a lot of time at the elementary school in Toronto where my wife was teaching. I enjoyed this so much that I enrolled in a two-year teacher training course – on my 50th birthday! After graduation and three years of supply teaching, I got my first class – two weeks after my wife retired! During my retirement years I have learned how to bake and usually bake cakes, cookies, scones etc. for others since we really should not be eating those things.

Since I am one of the very few folks in Ontario doing archaeobotanical studies, I felt that it was important for me to inform as many people as possible about this less well known field of studies. Therefore, I have taken advantage of any opportunity to speak to public or academic groups about my work.

JS: As an artist and photographer, what appeals to you in creating a visual image? What are all you considerations as you make such a creation?

RF: I see the extraordinary in the ordinary. My experience assists me in making decisions about composition, lighting, exceptionality, etc. Often a story unfolds in front of me, whether it is something in the natural world or when I am working with people in a solitary way or in groups or just wandering through an event. My artistic creations often take on a life of their own and I just follow instinctively. I have been planning a piece of art that makes connections between my work as an archaeobotanist and the peoples I have been studying for the past forty years. I have selected subjects which are meaningful to native people and my studies.

JS: Seeds. You seek them out and even hunt them down because, I take it, they are such rich indicators of our historical process. Fill us in about the importance of seeds past and present.

RF: Seeds are an indicator of plant use by people of the past for food, whether native or agricultural, fuel, cordage, housing, tools and medicinal purposes to name a few. This kind of information is not available with other aspects of archaeological research. Another interesting aspect of studying plants from the archaeological record is that we are able to study the origins and diffusion of cultivated plants, both here in the New World and the Old World.

Seeds of native plants are a rich source of proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins and minerals crucial to a balanced diet. Identifying plants from seeds, nut shells and wood provides us with an increasing knowledge of how people survived here in Ontario for the last 7,000 or more years. Identifying small bits of wood, for example, allows us to make statements about the importance of certain trees used for fuel and to examine changes in forest zones. Seeds and nut shells that we find allow us make statements about the availability of these plants and the seasonality of sites.

JS: Seeds are so small, so how exactly do you find them? How do seeds have impact upon how you visualize the world in your art?

RF: Because of the small size of the seeds, many of them are not readily visible. Archaeologists have to process archaeological soils using water flotation techniques which separate plant material from the soil before sending the resulting small parcels to me for examination. This technique reduces the volume of material to look through by 95%. Soil samples are taken from important site locations {garbage heaps, hearths etc.} and then ‘floated’ in water to separate the charred plant material from the soil. Materials that float are collected, dried, and packaged as the ‘Light Fraction’. This includes tiny seeds, nut shell and all manner of corn elements that includes cob segments, kernels, stalk fragment and ‘cupules’ {small pockets that contain the corn kernels on the cob}. Larger materials that sink, ‘Heavy Fraction’, include nut shells, charcoal and sometimes uncharred wood. The archaeology community generally sends me Light Fraction samples to analyze because they will provide the most botanical information. From time to time I have also examined Heavy Fraction and Screened material. This often provides additional botanical information and I have even identified a wooden bead from screened material from a 2,500 year old site in the Mississauga area.

After the field separation techniques have provided me with material to examine, I may have to further separate the material in a series of different sized sieves to make it easier to find seeds. That done, I identify seeds, nut shell and wood fragments based on their microscopic features. I look at their size, form, surface pattern, shape, and where they are attached to the plant. These characteristics all help me make an identification, with confidence, of most of the botanical material.

To answer the second part of your question, it is these characteristics that waft through my brain and comingle with those wonderful things going on in the right side of my brain. In some of my spare minutes I will commit pencil, pen and ink to paper to render my own impressions of these invisible patterns that only a few people in the world have privy to. So much to do, so little time. I am looking for a forty hour day so that I may have more time to do all the things I would like to do.

JS: Whatever you are doing, the process of finding out endlessly seems essential to you. How does such inherent need to explore and find out manifest itself in the activities you do?

RF: I guess that I am basically curious. I find that, if I am listening to music, drawing or painting or walking around taking pictures, I want to understand the process behind wherever my interests take me. Often I see the extra-ordinary in the ordinary. I see patterns everywhere.

JS: Tell us about maybe five or your discoveries of any kind that have been essential to your development, especially in the overlap of the sciences and the arts.

RF: One of the interesting things that I have noticed over the years is that I have a capacity and enthusiasm for learning new things. This ability has led me to where I am today. My academic career had me in university in my late twenties, early forties and early fifties. When I finished my master’s studies at York University, employment in archaeology was not forthcoming so I worked for Northern Telecom as an installer and thoroughly enjoyed it. I learned quickly how to do intricate wiring jobs. The temporary 90 day job lasted three and half years. After I left Nortel, I found out that I had been viewed by them as a valued worker.

When I was unemployed in my fifties, I took on a volunteer position at my wife’s school that led to teacher training studies at the Institute of Child Studies in Toronto. My interests in the arts were valuable while working with children or adults in the classroom because I was able to create activities and workshops. Before I even applied to teachers college, I gave workshops in archaeology and archaeobotany to elementary and high school teachers and I provided a two day mini-course in caricature and cartooning for the Gifted Program based on my collection of cartoon and cartoon history books. Immediately after getting my teaching certificate, I travelled to elementary and high schools around south central Ontario doing presentations for the Ontario Archaeological Society.

While I was teaching, I gave a paper at a symposium. I was one of two people using slides – I had back up overheads in case the projector didn’t work. The other presenter using slides and I were amazed at the Power Point presentations given by the students and other young people. Once I retired and found that people wanted me to give presentations to various groups, I realized how convenient it would be for me to learn it. So, I set about learning to use Power Point.

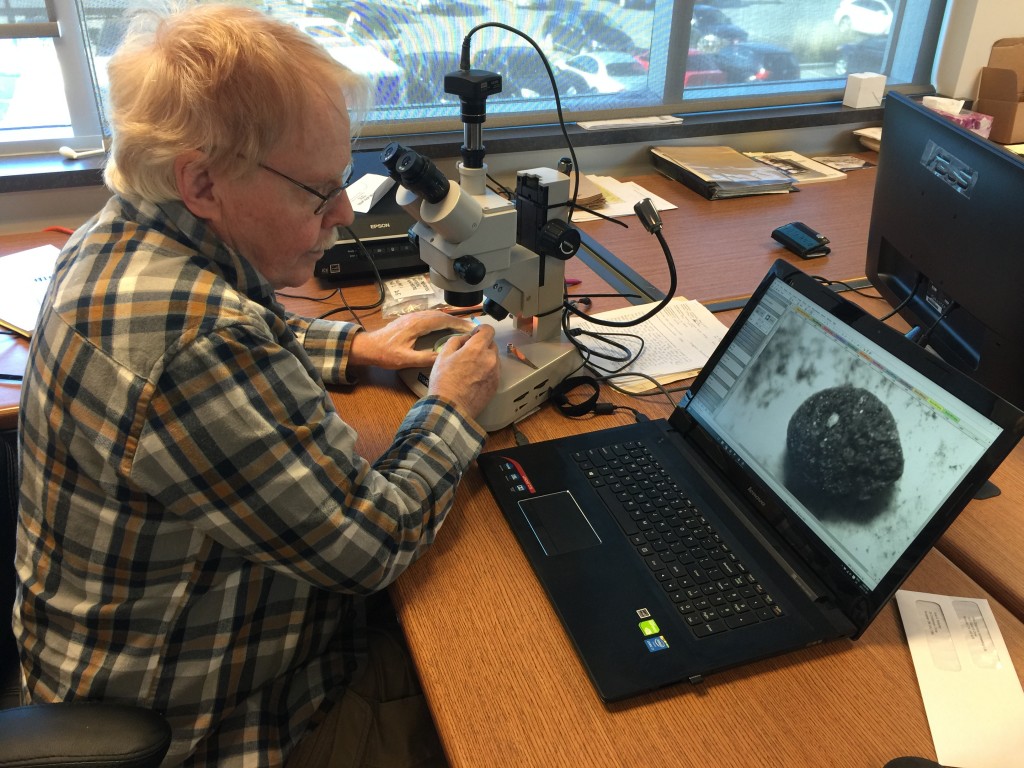

Since many of the materials I study are very small, I need to use a microscope. However, that makes it awkward to show a group of people what I see. I needed to have photographs to illustrate these things in my presentations. I had lenses for my camera to assist me in photographing some of the larger material, but, microscopic items were beyond my ability. Enter Richelle Moynahan of Wilfrid Laurier University and her brand new computer operated microscope which was capable of photographing minute particles. She needed materials to allow her to develop facility with this equipment and asked an archaeology professor if he knew anyone with materials which she could use for practice. As a result, I have photographs of a number of microscopic seeds which I have been able to use in reports and presentations. Subsequent to this, McMaster University opened the Sustainable Archaeology Lab in the Innovation Park facility. Catherine Paterson, the Operations Manager, has even newer equipment which she has used to photograph many more botanical items for me. More recently, Paul Racher of Archaeological Research Associates Limited invited me to use a new camera/microscope at his company in Ancaster. I have been going there for ‘Photo Phridays’ for several weeks and collecting a number of new images for my reports and presentations. As a result of my teacher training and years in the classroom, I think I have become a better ‘explainer’ with regard to talking to groups or individuals about all my interests.

JS: The notion and limits of time seem essential to your life and your thinking. Tell us about how you yourself experience time and how we as humans must adjust are concepts of time.

RF: Basically, the problem is that there is not enough time for all the things I want to do. As a result I am always having to leave one thing to go work on something else. This can be frustrating because I feel that some things get neglected. It would be nice if I didn’t have to sleep.

JS: You seem to be constantly turned on by the world you experience. Please explain this state of being, how it has impact on your creativity, and you manage to function among others who take life for granted and are not as inspired by life as you?

RF: I find that most everything is interesting and exciting. This allows me to be able to see how things can be connected and interpreted. I find that I tend to be drawn to people who have similar interests. Those people who don’t feel the same way tend to avoid me because they don’t want to be lectured at so I don’t have to worry about having to deal with them.

JS: What is the essence of teaching and learning?

RF: Sharing! Encouraging others to question and explore. Showing others the fun of learning.

JS: Tell us about your connection to native communities and how such contact has affected you as an artist and as a scientist.

RF: Despite being involved with pre-contact and contact sites for many years, I didn’t actually meet any First Nation folks until about twelve years ago. After that I volunteered to be part of the Monitor/Liaison training at both Six Nations of the Grand and the Mississaugas of the New Credit. Subsequent to that, I was invited several times to participate in the Historical, Cultural and Educational Gathering at New Credit which included elders, artists, story tellers, doctors, historians, archaeologists…

I’ve also enjoyed taking pictures at a Six Nation lacrosse game and of dancers in full regalia at both Six Nations of the Grand, Museum of Ontario Archaeology in London, and Mississaugas of the First Nation Pow Wows. Some of the photographs have been used by my wife for mixed media and water colour paintings. Since my retirement we have met many First Nation folks of different ages, casually and in the classroom, and appreciated being treated as elders by younger members of the communities.

JS: Which of your senses do you enjoy most and find the most rewarding? Why is this so?

RF: Sense of humour, because I enjoy that state of mind. I remember fondly when I was cartooning that I was always drawing with ‘punning’ intention. I often find that a sense of humour goes far when meeting people and can relieve tension in a new situation – especially mine. Close behind is a sense of curiosity.

Now that I am retired and working on being a lay-about (no time yet) I am reading about science on purpose. When I was younger I did not have the opportunity to finish high school and because I was taking technical subjects I missed out on English, physics, chemistry etc. I find the exploration of physics, astronomy and cosmology so fascinating and interesting. I have read and continue to read this aspect of science in my spare minute. I use that minute wisely.

JS: You suggest an interesting past, one that among other things includes figure skating and playing the five string banjo, so tell us about all the interesting things you have done, especially interesting stuff that you might not include on a CV.

RF: After being taken out of school after grade 11, I got a job as night messenger at CN Telecommunications in Toronto. This introduced me to some cat-sized rats in alley ways around the Union Station area while I was delivering inter office communications or going for coffee for the staff. My younger sister was involved in roller figure skating in Mimico at that time. She encouraged me to get involved as well during my free time. Eventually at CN I became a teletype operator and took over as a shift supervisor when I was 21. The introduction of a computer system in the late 60’s led to my first bout with unemployment. I noticed that U. of T. was going to accept adult students who did not necessarily qualify for admission. After taking a summer course in English at U. of T. and an effective reading course at York, I was admitted to U. of T. when I was twenty-six. I took a variety of general courses which might make me more employable. One of the last courses I took was field archaeology which led me to completely change my idea of what I wanted to do after school. I worked on various sites for the ministry which administered archaeological work. This took me out of Toronto and to various locations in north central Ontario and to university in Winnipeg for a few months (where I was exposed to the banjo).

Once I had developed skills in archaeobotany, I was hired by the Museum of Indian Archaeology in London to work on a site in Pickering which was the proposed area for the new (and later extinct) airport. This was the first large scale excavation in Ontario that used bull dozers to remove top soil. I collected and floated soil samples then packaged the resulting float residues for study. During this time I became involved with the Ontario Archaeological Society in London. Many years later I received the Society’s highest honour, the J. Norman Emerson Silver Medal for my contributions to the society and archaeological education.

I always enjoy visiting museums, art galleries, botanical gardens and archaeology sites wherever we go. One time at a museum on Cape Cod, I went to the washroom then found an archaeology lab where I was busy chatting for some time until my wife finally found me.

Throughout my life I have enjoyed reading. This has included comic books, science fiction stories and science and art magazines. I had amassed a large collection of cartoon and cartoon history books which eventually was donated to the Dundas Valley School of Art. I was exposed to stories and books aimed at elementary school students while I was teaching and found that I enjoyed many of them. Many science fiction, fantasy, and children’s stories have been made into films which I have also found enjoyable and have collected.

JS: How in your experience do the arts and science impact one on the other?

RF: Science focusses on patterns and organization. For instance, seeds and charcoal all have patterns that are species specific. This is what allows me to identify the archaeobotanical items which are sent to me. Art, whether it is visual or auditory, has to do with perceiving and reproducing those patterns as well as developing patterns which might not actually exist.

JS: I know you love science fiction, for one, so how about you describe some of you favourite films, books, and TV shows of any genre and tell us why they interest you. How do they influence you as a scientist and an artist?

RF: Yes, I enjoy science fiction. Some favourites are Forbidden Planet, The Day the Earth Stood Still, War of the Worlds, Star Trek, Star Wars, Jurassic Park… I enjoy watching science programs such as Cosmos, The Nature of Things, Nova, Nature etc. on television. The Choir, other concerts, and documentaries about arts and artists are also of interest to me. I like to see how people develop characters, plots and settings. The crossover between actual science and science fiction is interesting as is the visual art associated with it and the music used as background. I enjoy the use of animation and computer generated graphics in these films. In the reports which I prepare, I use charts and graphs to illustrated and explain my findings.

JS: Let’s use whatever personally meaningful criteria you have for creativity and ask you this: “How exactly are you creative?”

RF: My creativity has been with me since I was a wee lad. I remember copying comic book covers in detail with class mates at a young age. I can still recall copying several Walt Disney comic book covers which my father did not think I had done freehand but had actually traced it. I continued to play with drawing and sketching much of what was around me, especially trees and plants. I have kept this interest up during my whole life, but not seriously. I never seemed to have enough time.

Whatever it is I am doing – baking, taking pictures, drawing, painting – I try to modify, alter and change it according to how I react to elements of that specific endeavour.

JS: Why should all people care about archaeobotany? Why should all people care about the arts?

RF: Archaeobotany tells us stories of the environment and how it affected and was modified by those who lived before us. We can see how use of plants from the environment led people to the development of agriculture. It helps us to see that they were much like us.

The arts show us the heart and imagination of people, how people dealt with communication and with the spiritual. There is something intrinsically special about being creative, about telling stories, portraying life as it is and how it could be.

JS: What projects are you working on at this moment and why these?

RF: On January 21st a group of seniors from the Misssissaugas of the New Credit are taking a bus trip to our house. I will be presenting a power point presentation that includes a 7,000 year perspective of plant use in Ontario. I will also focus on plants with medicinal properties to illustrate the availability of these plants to their ancestors.

In mid-January I begin an art course at the Dundas Valley School of arts to work on current art projects that illustrate a connection with plants from the archaeological record and how they connect with my understanding of the spiritual world. This current project has also been nurtured by my interest in native painting, especially ‘Woodland’ painting.

I am also involved with analysis of plant material from an early 17th century Huron/Wendat site in Simcoe County. This is being done for Gary Warrick and Bonnie Glencross at Wilfrid Laurier University. This project is the largest I have been involved with for the last several years. It incorporates examination of carbonized seeds, nut shell fragments and wood from more than a hundred samples. What is unique about this project is that all the material is from four middens {garbage heaps}. This is the first time I have had material to analyze from a detailed archaeological context. The archaeologists have provided material excavated in 10cm levels from each midden. This will enable me to identify plants in each level. I will then be able to compare and contrast each midden and level in detail.

JS: Do you ever sleep?

RF: Yes! I generally need about seven hours a night with occasional afternoon naps. I have even been known to have my “afternoon nap” at 11 am – if I had been working down in the ‘dungeon’ from 3 or 4 am. I often miss about a half of evening TV shows because I nod off. I am often motivated to get up during the night to attend to creative notions that come to me in dreams or on current projects.

JS: Tell us about your working space, why it serves you well and how you might improve it.

RF: “The Dungeon” was a section of the basement that my mother-in-law had finished so that I would have part as workspace and my wife would have the other for a studio. However, my work managed to spread out and take over the entire space. In fact, it has started sneaking into the main part of the basement as well. In the dungeon, I have a section for microscopy, a computer/monitor/printer table, several tables for layout space, a storage closet and LOTS of book shelves. Other folding tables are put into use when I need extra layout space for a project. More space and better lighting would be an improvement as well as consistent heating.