JAMES STRECKER: Please tell us about one or more projects that you have been working on or have recently completed. Why exactly do they matter to you and why should they matter to us?

DANIEL TAYLOR: Jean Vanier reminds us that our meaningful actions can be put at the service of the divine and of love. There is a project close to my heart that was born from a trip I took a few months ago. I travelled to Africa with a delegation on a mission for Education and Health, and similar to my time in South America, I was a witness to and confronted by abject poverty, tremendous courage, and hope. I met with women at a clinic who have experienced obstetric fistulas and who, having been rejected by their community, have been taken in by the RAM Clinic and Foundation. I met with students dedicating their life to sharing their music across the globe.

On these trips, I was asked to sing recitals for the Presidents in major outdoor live televised events before traveling to both central and remote locations to teach. In the back of my mind, I have always wondered if there was something more I could do – something tangible. I have since been building a scholarship fund for studies in Early Music at the University of Toronto for African students (and for all students) to come to Canada to read music and I am interested in developing a national network of support.

Lastly, I have a major international recording with 20 musicians that is dedicated to children fighting cancer, a cause that two of my dearest friends – a doctor and his educator partner – have dedicated their lives to. Out of all my most recent recordings, I am drawn to this particular project because of its focus on children, birth, and death. I am keen to examine the intersections between music, health and prayer. It is our calling to transform what is not into what is that brings us closer.

JS: How did doing these projects change you as a person and as a creator?

DT: These projects have reminded me that collaboration is the indispensable quality of creativity. These experiences and the entire recording process – including researching the scores, travel and a lot of reading – influenced how I look at my life and aloneness, how I observe life in order to learn about my humanity and about the world.

JS: What might others not understand or appreciate about the work you produce or do?

DT: Beauty can be seen through more than one lens. Music can help us imagine and hope for a better future. Acceptance of vulnerability and of not knowing is essential for growth. Within the collaborative process, there is a sense of discovery that comes from working with a variety of individuals and that part cannot be seen in the final recording or product.

Every concert and every one of my recordings have represented hundreds of hours of work and are a testament to many, many kind and gifted individuals. The next three recordings continue our search for meaning. I believe music can heal and is a universal language.

JS: What are the most important parts of yourself that you put into your work?

DT: I think that would be my heart.

JS: What are your biggest challenges as a creative person?

DT: Well, I just put my heart into it, so next is my soul… they sort of go together, don’t they?

The next challenge is not being at home.

Then there is the idea of ‘existing in love and unlocking the prison of our egoism.’ When the doors are unlocked, others sometimes feel the need to come in uninvited and bring their suffering to us because they are full of fear. So, with being vulnerable, we open ourselves to criticism.

We then need to understand that when we provoke our listens to consider shifting their perspective, the listener can gain the ability to become empathetic and perhaps even to find purpose and meaning for what they do.

JS: Imagine that you are meeting two or three people, living or dead, whom you admire because of their work in your form of artistic expression. What would you say to them and what would they say to you?

DT: Friedrich Nietzsche, William Shakespeare – “I have a lot of questions”. They nod knowingly.

Jonathan Miller – “Please tell me more.” He nods knowingly.

Virginia Woolf and Arthur Miller – I would just listen.

JS: Please describe at least one major turning point in your life that helped to make you who you are as a creative artist.

DT: A few years ago, a family member experienced a life-changing injury that rendered him disabled. Now, one of our greatest challenges is to help him find a place in our society along with the proper support. There is an ‘othering’ that targets the disabled as well as other minorities such as the LGBTQ+ communities and undergirds disputes, conflicts, disease and hunger. Many are isolated and may feel like they will never be loved, but I find those who are disadvantaged have the possibility to show us how to love. If I seem less interested in the politics of our industry and of the endless chatter of a few of the university academics, this may be the main reason why.

A few other moments come to mind when I think of being an artist: my first concert with Jeanne Lamon leading Tafelmusik, the BBC Proms, the Met and singing at a Pow wow, Ralph Fiennes, Michael Chance and Dame Emma Kirkby. The Cirque du Soleil – very cool! There isn’t really one moment that I would point to – I am thankful for many of my friends and guides I have met on this journey.

JS: What are the hardest things for an outsider to understand about your life as a person in the arts?

DT: I am a flawed and weak person surrounded by a chaotic world, and I have lived long enough to know this. I recognize that there is a fragility in my singing, in my conducting, and in my teaching that leaves some people uncomfortable.

Vulnerability in performance, however, draws us to the performer. I am studying practice techniques that help colleagues, students and all of us be more truthful in the moment and speak our truth in a professional, dramatic and honest way.

I believe in building opportunities for my colleagues and students and I believe an experiential teaching model is vital. I also believe in my students and I do not and will not treat them as infants. I believe in their power and I work within the realm of understanding that positive boundaries outline what is explorable – the imagination and the human spirit can then lead them to achieve the extraordinary.

As a student, I struggled with illness and had to work to find balance. I worry that there is, at times, more harm than good being done in the name of education: increased pressures on students encourages further complexity and this complexity actually causes more suffering – there is a true epidemic of anxiety among today’s students. We need to find an improved vocabulary to communicate with one another.

JS: Please tell us what you haven’t attempted as yet that you would like to do in the arts? Why the delay so far?

DT: I think that the last moment of ambition I had was when I was a child and thought I had super powers and could jump walls. I ran into that wall back then. Sometimes, I hope that those walls aren’t there any more… but they may be.

JS: If you could re-live your life in the arts, how would you change it and why?

DT: I have been fortunate. I suppose that there have been times when I would have wished that I had the presence of mind and clarity of mind to make better decisions.

JS: Let’s talk about the state of the arts in today’s society, including the forms in which you work. What specifically gives you hope and what specifically do you find depressing?

DT: The state of the arts today is somewhat bleak. One need only look towards the downward trend of sales at our biggest opera houses, the mismanagement of some of the leading recording labels, the conveyor belt young artist training and the lack of unity within our community to know something isn’t right. My hope is that the paradigm for the existing model will shift.

This goes hand in hand, if you ask me, with what is going on in Ontario and Quebec right now. I would say that adversity and faith play key roles in our worldly struggle, and here in Canada these seem at times to be translated into misplaced social outrage that undermines meaningful actions. Our own Provincial Government works steadily to undermine vital programs such as healthcare, affordable housing and education resulting in a skewed landscape of unequal opportunity while in Quebec, the Charter of Values disregards human dignity. We need more kindness and more love and respect for others.

JS: What exactly do you like about the work you create and/or do?

DT: I would like to address this indirectly. A few years ago, a man wrote to me about his husband and shared with me that every evening, they would play one of my discs in the background as they made dinner together at their cottage. That summer, his husband was very unwell and the needed to be away from the world – the breeze from the lake and the music transported them. One night, his husband asked him to open the windows of his house and turn up the music – and then he said goodbye and he passed away.

JS: In your creative life thus far, what have been the most helpful comments you have heard about your work?

DT: “Be quiet.” “Don’t judge.” “Listen.”

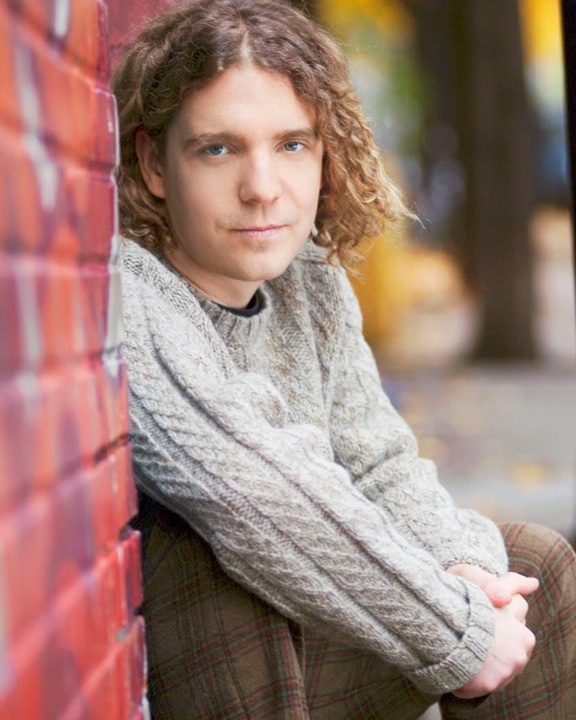

JS: Current information: Daniel Taylor appears this June with the Victoria Conservatory of Music before joining the Festival of Music and Beyond in Ottawa in recital and conducting Handel Dixit Dominus, in recital at the Elora Festival and in recital and conducting Monteverdi Madrigals with the Toronto Summer Music Festival. He also returns to the UK for concerts and to teach and perform at the Siena Liberal Arts University in Italy. The Fall brings him across North America in concerts and recitals and celebrates his return to the title role in Gluck’s Orfeo at the Teatro Col