From my archives, here’s a two part diary article I wrote on my visit to London three years ago for an alternative newspaper in Hamilton. It is long but, London being what it is, it could have been much longer.

LONDON: A CULTURAL DIARY PART I

Ten days of the arts in London, one of the world’s great cultural centres, can seem richer, as James Strecker recently discovered, than a year of the arts offered in other cities. This month, Part I of Strecker’s Cultural Diary reviews current productions, recitals, concerts and exhibitions.

Although the overture to Matilde di Shabran –with its playful ardor and bombast, urgent pulse, and nudge-nudge cascading rush to conclusion- is lighthearted Rossini to be sure, we are soon warned that “fierce Corradino loathes every woman,” that “where Corradino reigns, death is never far away, ” that melodrama is in the works. And much else, we happily discover at the Royal Opera House. Although absent from Covent Garden for over 150 years and rather unknown, this Rossini hybrid of sorts features dazzling coloratura writing for soloists, delicious servings of vocal groupings, and a plot with much room for individual characterization. Peruvian Juan Diego Flórez, as the dreaded misogynist Corradino, sings with a distinct and silky ring in his renowned and thrilling high notes and maintains true vocal beauty while suggesting nuances of character, sometimes through shadings of timbre and sometimes through the seemingly tossed off scales he dispenses with unsettling ease. A few months ago BBC Music Magazine elected him one of the top 20 tenors of all time and tonight we hear why. As Matilde, the Polish soprano Aleksandra Kurzak possesses a slightly fleshy and tonally rich voice, one also made of finest crystal as it soars even-toned into the upper registers. Her subtlety, her sense of comic proportion, her range, her naturalness, her instinct for underplaying and acting by reacting all make her a consummate creature of the stage –and she is quintessentially cute. Bulgarian mezzo Vesselina Kasarova’s arresting voice resonates with nobility and deep-in-the-earth profundity and, with seamless fluidity, she reaches a nuanced timbre and simultaneous textures of feeling up high that suggest a genuine painful longing. So, vocally, this is an evening I’ll never forget.

However, there is an irksome side to this production. Sergio Tramonti’s double intertwined spiral staircases, which require ascent and descent with singers remote and with backs to the audience, works against the production’s fluidity and ease; singers incessantly climb up these stairs and then climb down these stairs and all the noise distracts from the singing. Secondly, Rossini is inherently funny and a director should use this humour to advantage and not arbitrarily push tongue-in-cheek into exaggeration as Mario Martone does. Like Cary Grant, say, Florez possesses inherent poise from which humour arises in trying to hold it together, not going the route of repetitious buffoonery. Too often in the role of Corradino, we see direction at work and Florez with business imposed upon him, which makes no sense since Florez is indeed capable -with facial expressions that are indeed scary with demonic rage and understated fury or full of delightful confusion and boyish charm –of compelling characterization. He’s a more subtle actor than his director allows him to be. On the other hand, the opera critic from Paris beside me found the handling of Florez hilarious –but then, the French hold Jerry Lewis in high esteem, don’t they?

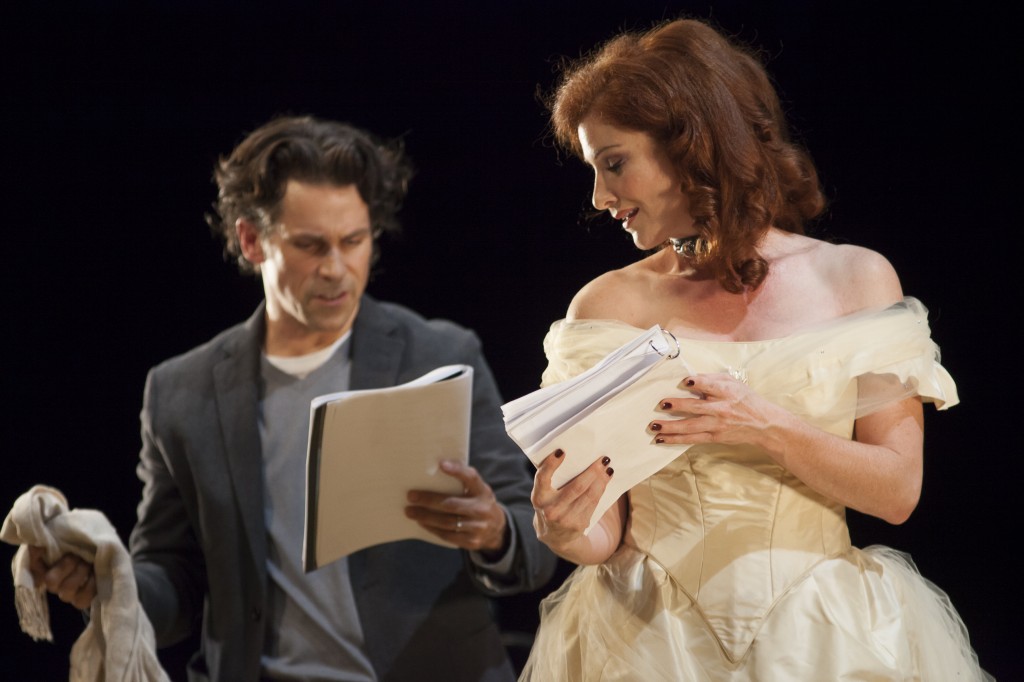

Like the Dadaists/Surrealists, The English National Opera’s production of Handel’s Partenope, here set in a salon of 1920s Paris, pushes the audience over and over to accept incoherence, audacity, and absurdity, yet we feel anchored by Handel’s musical momentum and idiomatic richness throughout and are thoroughly entertained. Credit an outstanding cast of singers with voices of inherent emotional richness and security in tonal focus, with rarely a blared edge that bends out of shape in upper registers. Credit also how this production feeds on the humorous potential of Handel by domesticating it into a modern setting, thus isolating the implicit pomp in a context too small to contain it, with much humour the result. Above all, credit Handel, Beethoven’s favourite composer, an undeniable genius. We’re in the Coliseum which was built in 1904 for 350,000 pounds and which, in the orchestra, feels like the inside of an inside-out wedding cake, so already we are in a bizarre mood for whatever mind-bending is to come. And there is, in Christopher Alden’s production, much cross-dressing and sexual fun, with women playing men, women playing women disguised as men, a lot of kissing in every direction, much sexual innuendo, and a fluid eroticism throughout. “Things aren’t quite what they seem” says he, as he feels her disguised female breast beneath male attire; “Who could plunge a sword in that fair breast?” asks he and we see a film of –what else?- a breast. Yes, there is indeed a lot of tit in this show.

And don’t forget –what, in Handel?!- the bathroom humour, John Mark Ainsley’s aria as he sits on the loo or a duet as one sits on the loo reading a broadsheet and one unrolls toilet paper. And –why not?- Rosemary Joshua as Partenope, with three suitors, who dons a gas mask to end an aria and Amanda Holden’s translation that contains lines like “You little shit!” and “Will you shut up?” As said, the singing is notable: a perky Joshua delivers Handel’s staccato runs with assertive aplomb and loyalty to dramatic demands; Ainsley as Emilio offers singing of purity and polish, even as he stalks and exposes, through Man Ray images, what concealed appetites and inner realities wait to be revealed around him. My happy discovery tonight is Christine Rice who, with rich and potent voice, with fluid, warm and delicate shadings, reveals a rare quality of being monumental and intimate at once. One holds one’s breath to hear where voice and emotion will go next, in their poignant union, as she sings.

This week is also unbelievable in the number of outstanding vocal recitals available. At the Barbican, it’s an evening of Scenes from Viennese Operettas, with Les Musiciens du Louvre-Grenoble, on period instruments, conducted for frenzy by Marc Minkowski and sung by mezzo Angelika Kirchschlager and baritone Simon Keenlyside. Minkowski does Strauss with swagger and punch, although often too disruptively emphatic in the latter. Kirchschlager’s voice is one of nimble richness that dances with an opulent swirl, one that sings as if it has the right to sing. She sports a huge fun mop of a hairdo and she, born in Salzburg, embodies Viennese coquettish flirtation with broad smile and deftly raised eyebrow –her sexy dress is the knockout punch and so we’re in love! Keenlyside is a rock solid baritone who pulls off vocally uplifting, crisp and full-bodied, solos -I suspect that he is a tenor at heart because he certainly thrills like one. Yet Keenlyside carries his momentum of line in lilting steps as he sings these Viennese favourites by Strauss, Suppe, Lehar and Kalman. He even uses his spilled beer on the floor to literally add froth to one character.

At Wigmore Hall, it’s soprano Diana Damrau in a recital of Berg, Barber, Strauss, and Iain Bell. Her Berg is presented with an evocative tonal palette that is thrillingly operatic or creeps through darkness like a haunting whisper. In Barber one feels the psyche working itself out, exploring every unsaid, inviting the unreal. Next, in Bell’s Daughters of Britannia, we have a fiery Boudicca, a Maid Marian full of longing, and also in Morgause, Guinevere, and Lady Godiva, Damrau seems to think and feel through the sound she makes as much as the meaning of words. In Strauss, she has an instinct –or is it need?- for drama as, with her voice, she paints lush images in sound and then delights herself in a lighter Cupid. I love listening to her, but am unsure, as yet, how much she moves my emotions; she aims for perfection, but emotion is rarely perfect and it messes up the clean edges of technique. Damrau’s is a career to watch, to hear what route she will go with it. Afterwards I tell her that her Queen of the Night aria on her Mozart CD is one of the most ferocious I’ve heard, which indeed it is. She eyes me and, out of the blue, goes “grrrrrrr!” She seems a fun gal.

Czech mezzo Magdalena Kozena, at the Barbican, in a recital titled like her latest CD of Czech songs, Songs My Mother Taught Me, is a singer who has moved me deeply and without fail since I first heard her sing just a few bars of Bach several years ago. And tonight this recital fixates me in naked emotion. Perhaps it’s these classical re-shapings of Czech folksongs that summon up the ghost of a Bohemian grandmother I never knew, perhaps it’s Kozena’s refusal to sell out feeling to technique but instead to inhabit the life of each character as her own, perhaps it’s because there’s a genuine down-to-earth celebration of flesh and sweat and spirit in her singing, perhaps it’s because she’s every archetypal village girl betrayed by every unfaithful lover in every tragic, witty or ironic or folksong I’ve known, but I’m in another world, the one her singing vividly creates. “Your singing means so much,” I tell her afterwards; I can think of nothing more to say, for I have been too unsettled by her art, by her honesty of feeling.

Speaking of folk tradition, at the Royal Festival Hall, with Richard Hickox conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra, it’s a megadose of Vaughan Williams –Symphonies Five, Six and Nine, plus Three Shakespeare Songs, plus Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis. The latter opens with the offstage singing of the hymn tune from which Williams developed his Fantasia; it carries a sense of benediction that then time-leaps into a contemporary pastoral spirit of Vaughan Williams’ score, one that is lush and green in sound, rooted to the earth and part of some eternity too, and always singing, always singing. Whatever the composer’s experimentation in the symphonies, whatever breaking of musical bounds, I hear the land of centuries giving voice here and hold my breath as I feel an atmosphere infused with spirits, themselves made of grass. A symphonic concert, yes, but in a deeper sense, another vocal recital of many voices from the earth.

For forty years I have come to London for theatre more than anything else –my M.A. in Drama has had some effect, I guess- and I’ve been lucky to see the likes of Gielgud, Olivier, Scofield, Dench, Redgrave as in Vanessa, Plowright, Kingsley, Richardson and also many productions that made me see theatre anew with more scope and delight. Only three plays this time, but first it’s Michael Gambon as Hirst in Pinter’s No Man’s Land with David Bradley brilliant as a skin-sticking Spooner. With Pinter, as always, it’s everyday aggression, volatile coexistence, a tennis match of power, intrusion and assimilation or denial, arbitrary attacks, inherent seediness, monologues out of nowhere, language that means and intends so much or means and intends nothing. Pinter’s trick is to make us feel we might know what’s going on and then undermine us with doubts about reality, though nowadays Pinter is modern classic stuff and the audience laughs in the comfort of familiarity. In Pinter, Gambon, like an unpredictable volcano, says little yet implies volumes of menace. But always with Gambon, it’s his voice, monumental like stone and even when gentle still monumental. It’s a voice that knows danger, a voice that that doesn’t bend, a voice that seems indifferent in grandeur. The usherette is a third year student in classical studies and film who says of the production: “I wasn’t too keen at first, but now, after six weeks, I find it funny and don’t space out.”

At the Gielgud Theatre, Pirandello’s Six Chracters in Search of an Author, in a new version by its very “hot” director Rupert Goold, proves to be, in its theatrically dynamic reworking to the present day, one of the most intellectually invigorating experiences I’ve had in theatre. The “abandoned” characters arrive during the making of a television documentary, not a play, and it’s then that the head’s decree, “Keep it real” becomes ominous. Pirandello’s play is one of modern drama’s most disturbing mirrors of the modern psyche. We live simultaneous dimensions, not a constancy of one reality from which to assess others, and a character’s question “You watch us but who watches you?”

shows that what we treat as fixed reality is fiction for another, something to judge if indeed it interests another at all beyond indifference. Goold’s reworking of Pirandello makes us, the audience, part of the artwork.

At the Soho Theatre, the play, Emotion, is a collaborative effort between neuropsychologist Paul Brooks and playwright Mick Gordon that explores how we use reason to make moral decisions, but remain “puppets of our emotions” and in constant sexual need. There is much hilarity here, say when we, and not his attractive female client, hear the shrink’s thoughts about her “sucking my cock.” The scene with the shrink concealing his post-masturbation wad of Kleenex is a riot and there is food for the mind here too in lines like “We must choose to be free to choose.” Like Pinter and Pirandello, this new play confirms anew that all is flux, that,whatever our illusions, we are not in control of ourselves and our destinies.

The Poetry International Series 2008 features tonight, in the Purcell Room of Southbank, four poets at thirty minutes each. The first is Andrew Motion, who previously has stated that having the position of current Poet Laureate of England, has been “very, very damaging to my work…. I dried up completely five years ago.” Happily he now tells us that “he has written more in eighteen months than in years” and reads poems based upon the words of British soldiers in World War I, the last of which ends “Then the silence will sing to me.” Russian poet Katia Kapovich explains “When I had my first dream in English and cried in English, I thought it was time that I could write in English.” To a waitress who questioned her ability to even speak in English, Kapovich responded, “ I have two books in this friggin’ language. What do you have?” Of Americans, she says “I don’t quite understand what they do.” After the modulated, fireside quality of Moniza Alvi’s humane reading, Spaniard Joan Margarit speaks in potent incantation, in Spanish, of his dead daughter and much else from the trenches of daily life and we are deeply moved. He seems more visibly raw than the others, less prone to control of his feelings.

It’s also a week of amazing exhibitions. By accident, I begin the Francis Bacon show at the end, a 6 by 5 foot canvas titled “Blood on Pavement” which feels like a body dropped from a great height that has splattered with a thud and still continues to exist. Bacon’s bodies seem to have a layer or two of skin removed and the large canvases invite one to enter them and coexist with these pummeled human remains. One figure from 1964 sits on a toilet with spine exposed, another is a boxer smashed head first to the floor with mouth wide open. There are numerous portraits of George Dyer, Bacon’s “closest companion,” who committed suicide in 1971. The paintings from the ‘50s are more distinct as bodies, much darker, and they lack the sweep of obliteration and the inherent horror of later canvases which, strangely, have prettier hues and seem to use blood and nerve as their pigment. I once sent John Gielgud my new book of poems which contained, as well as one about Gielgud, a poem about a previous Bacon show, right here at the Tate, I believe. Gielgud wrote back that he’d always wanted his portrait done by Bacon, but felt he’d be horrified at the finished painting. Well, Bacon has reached under my self-protecting illusions about existence and exhausted me. As a result, I can only stroll for a short time through the marvelous Tate Britain collection of Hogarth, Stubbs, Blake, Fuseli, Constable, Lucian Freud. In the main hall of the Tate Gallery, ten runners in gym attire run from end to end, one at a time; they are intended as a work of art; they have caused much controversy, I am told.

Renaissance Faces at the National Gallery satisfies, for now, my obsession with faces. I love to go searching in the eyes of portraits, maybe because, as the note beside Messina’s Portrait of a Man from 1475 explains, some believed that “the soul was visible through the eyes.” So who can explain the ambiguous soul of Bellini’s Doge, a portrait I’ve known most of my life. Or that of Martin van Heemskerck’s pregnant Lady with Spindle, a woman described as virtuous, but whose eyes suggest an interesting worldly life too

-and one wonders at the father of her child. I don’t envy Marsilio Cassotti’s wife Fantina in Lotto’s Wedding Portrait, since hubby seems a soulless and bloated bore. Lombardi’s Young Couple in marble relief suggests a seductive sexual ambiguity –initially I, wrongly, see two women, lovers in love and no doubt about it. And then the touching intergenerational intimacy of Ghirlandaio’s Old Man with his Grandson, full of love and warmth and trust. Vecchio’s La Bella –an idealized portrait of a Venetian noblewoman- was celebrated in Renaissance poetry of the time. The woman beside me quips, “I’d say she’s accessible, she’s up for it. How would you like to get a look like that across from you on the tube?” Well, sure, I could live with that.

Later, at the ICA, the Institute of Contemporary Arts on The Mall, I find myself lying on the floor, I find myself dancing alone around the room, surrounded by eight speakers that give forth rhythms that work along side and within other rhythms, human cries and human singing, room shaking thumps, sensuous plucking of strings. These sounds find in me, pound into me, origins I do not know. People come and go and stay only a minute or two, but my body has come alive as I sit and move within this sound installation by Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi called Šuillakku for which, to create it he “spent two years immersed in the language and rituals of the Assyrians.” The work employs a great number of musical instruments and features a chorus Cuoghi created “by multiplying and mutating his own voice into an extraordinarily potent, cacophonous assault.” He was inspired by Mesopotamia of the seventh century B. C. and Assyrian lamentations to their gods; somehow he has found the now of my existence and nailed it to the wall. I feel found out and released.

LONDON: A CULTURAL DIARY PART II

In the second part of his account, James Strecker visits some of London’s cultural institutions and listens to the voices of the city.

The British Museum, perhaps London’s most visited attraction, houses three million prints and drawings dating from 1400 to the present, and in the British Sculpture Drawings exhibition “the only known surviving cartoon by Michelangelo” is taller than I. A walk through the British Museum is, of course, a stroll among the dead and their artifacts, one that offers intriguing discoveries with each visit. There’s a wall painting from 6th century A. D. Egypt of the three martyred “children of the furnace,” Ramses IX with eyebrows carved directly from the sycamore figure and not inlaid, a mummified eel, a mummy that “originally lay in the coffin on its left side, the eyes aligned with the eyes painted on the coffin,” a Mesopotamian copper bull from 2500 B. C. whose eyes look through me as I walk before it. At the Rosetta Stone I read that in these hieroglyphs the “first three signs record the sounds miw….the word is derived from the cat’s meow.” Among the Elgin Marbles I realize that I know no other sculpture with as many folds as the dress of Aphrodite as she lies on the lap of her mother Diane. In the Assyrian room I meet a life size attendant god from Nimrod of 810 B. C. who “stood outside a doorway in the temple of Nabu, god of writing.”Writing has its own god!? And then a display of archeological sites destroyed by the bombs of that vermin George Bush.

At the British Library’s display of literary works in original manuscripts, many authors and their words come alive in these numerous treasures. This is the ink they wrote upon these very pages and, as one reads, one feels part of careful and intimate acts of writing long ago. Here the blotches on Beethoven’s Violin Sonata show creativity in process, a document alleged to be in Shakespeare’s own hand, Hardy’s Tess with many lines inked out and corrected, the manuscript of Jane Eyre in miniscule hand, Lenin’s Application for a British Museum Reader’s ticket and a note that it was there where he first met Trotsky, Captain Cook’s densely written journal, Sir Thomas More’s last letter to Henry VIII a year before he was beheaded, a letter by Isaac Newton. I do a quick handwriting analysis of McCartney’s and Lennon’s writing and understand, to a degree, the tension between them..

One often sees something new in familiar places and, at the National Portrait Gallery, my first is revelation is Richard III with his pinched lips and eyes pierced with inward torment I’d never noticed before. Then Keats, who looks like a seated twig, beside Coleridge and Byron, and Jane Austen,” who compared her writing to painting,” in a small portrait that Walter Scott found to be a “strong resemblance.” Byron seems an arrogant self-promoter, Edmund Kean as Brutus explodes inwardly, Congreve points at something off-canvas, perhaps human folly, and the bust of Pope, which Walpole described as “very like him,” stares with eyes of ice into mine. Priestley, who discovered oxygen, appears in a rare –for the Gallery- pastel of superb technical precision. I check out the Bronte sisters with their scrutinizing eyes, the Brownings, he at 46 and she at 52 and facing each other, Robert Louis Stevenson sitting where he smoked and drank coffee. Henry Irving seems sprawled and spontaneous in only two sittings, Virginia Woolf seems prissy and Vanessa Bell just plain unhappy, while Dylan Thomas, at twenty-three, looks chubby and girlish. I always fall in love in this gallery –this time it is the dignified and confident Louis Jopling who died in 1933 and last time it was sexy and brattish Lady Colin Campbell who departed in 1911. Julie Barlow, who does talks and tours and always considers “the life behind a portrait” chooses Queen Henrietta Maria, who was “very much in love with Charles I,” her favourite portrait in the gallery. I crawl over groups of schoolchildren on the floor to visit Britain: A National Portrait, which includes World War I poets, and leave overwhelmed by all the relationships these portraits demand of a viewer just to look at them..

If you need proof that The National Gallery holds one of the world’s great collections, consider the wall of Van Goghs, the wall of Cezannes, Renoir’s The Umbrellas with its deep blues and the woman with her deep, deep, deep black eyes, the clarity of Manet, a “New Acquisition” of Monet’s Water Lilies, Setting Sun, which makes the eye fight between depiction and paint as paint, Gericault, Daumier, Gainsborough, , Hogarth’s The Graham Children with their lunatic cat, Watteau, Turner’s Temeraire which was chosen by poll as “The Greatest Painting in Britain,” Hogarth’s Mariage a la Mode, the sensual forms of Boticelli, The Toilet of Venus by Velazquez with perhaps the most beautiful naked hips in art, and Filippino Lippi’s Virgin and Child. And the painting that has centred me in some kind of serenity over the past forty years, Adoration of the Shepherds from about 1640 by one of the Le Nain Brothers, Antoine, Louis or Mathieu. I can’t imagine a more wisely self-contained Virgin, here with fingers like stems, and I notice anew the beautiful tan tone of the cow, the eyes of the donkey so concerned as if he sees the future, the slightly startled angel, the intense and yet peaceful concentration of each figure. I realize the Virgin is wearing a black shawl I haven’t noticed in forty years –why is that? I leave and, as I walk through Trafalgar Square, say “I love you” into the night, to no one in particular.

On a wall in the Tate Modern, the enlarged signatures of great modern artists allow for some handwriting analysis: Giacometti was self-conscious, neither Calder nor Monet was sensitive to criticism, Picasso and Bacon didn’t readily spill the beans as to what they were thinking, I discover. In the first gallery, with Carl Andre’s 1980 “Steel and Copper Plates on the Floor,” we are in the world of what I dread most –those artist’s statements that Tom Wolfe once mocked so well in his book The Painted Word. Why the need for statements? In what other form of art does the creator attach an explanation of raison d’etre to his or her work? Why not just show me the stuff and let me work it out? Another room and too much visual gimmickry here posing as concept –again must I be told what my experience is? A whole room installation titled “Thirty Pieces of Silver” inspires animated curiosity from a class of kids and there is much pointing and many “oooooohs.” And they do so, they really get into this creation, without reading this explanation on the wall: “Cornelia Parker is known for works in which she appropriates objects and subjects them to acts of violence. She expresses layers of meaning with them.” I find writing like that to be a straightjacket to one’s imagination. Poor kids in front of a Lichtenstein with a teacher who says, “The word ‘Wham’ is painted really big as if it is loud.” Tell them something they don’t already know, lady! Don’t patronize them.

But thank you, Marizio Cattelan, whose Ave Maria is three arms extended from the wall in a Hitler salute. This is fresh; this is creatively clever. And I love the title of the next room: “Surrealism and Beyond.” And what might that be, beyond surrealism? Then the Bonnards and a celebration of colour, of dimensional ambiguity, of composition, of life; this is painting for painters, this is a painter who painted with his senses. And a realization, next, as I pass wonderfully intriguing pieces by Miro, Appel, Gorky, Dali, Picasso, that postcards and books always change the intended dullness of some paintings into a neon brightness and thus betray them. The artist intends one colour and the world, through reproduction, knows another. Then perfect Giacometti who found his uniqueness, who still kept searching and searching. And I love those bananas by de Chirico, never noticed those before. But it’s Barbara Hepworth’s Forms in Echelon of 1938, two parallel forms in wood that, with their subtlety in placement and shaping and sublime simplicity, stop me in my tracks. What skill and wisdom to make do with so little! I spend half an hour with this piece and, in a state of awe, touch it, over and over, with my eyes. It is too beautiful.

There are countless buildings in London, each with volumes of history. St Paul’s Covent Garden, the setting for the opening of Shaw’s Pygmalion, is known as the Actor’s Church. Here you’ll find Ellen Terry’s ashes, the remains of the first victim of the Great Plague of London, Mary Fenn “who departed this life 14 of September 1648, and the grave of “musician and parishioner” Thomas Arne who wrote Rule Britannia. There are many plaques in tribute to actors on the walls, many with quotes from plays -Vivien Leigh, Sir Noel Coward, Sir Terrence Rattigan, Boris Karloff, Edith Evans- and the place is kept in order by Father Simon and his two cats, Inigo and Jones. At Handel House, where the composer lived from1723 until his death in 1759, one learns in his bedroom that “men wore their hair sort to discourage lice” and that in this “upwardly mobile” and fashion-obsessive time, the affluent needed “a room dedicated to the function of dressing.” The bed is short because people slept half upright “to aid digestion.” It was a time when soprano divas and their factions did battle and Faustina Bordini whose portrait hangs here, and for whom Handel wrote Alessandro, seems a thorough bitch. A countertenor rehearses in one room as Stefanie True, a soprano from Cornwall (Ontario, that is) and now studying in The Hague, listens. Portraits of Jimi Hendrix hang in another room because, in 1969 for three months, Hendrix lived next door. Handel wrote Messiah here and Terry, who sells admission tickets downstairs, says, “sometimes I go through that room and imagine him writing those millions of notes.” Yes, I wonder how Handel got from beginning to end of Messiah in this room. Did he look down at the grain in these floorboards and daydream for a moment when imagination took a breather on him?

A backstage tour of the Royal Opera House is a delightful overload of information. The first theatre on this location was built in 1732 and paid for by proceeds from the very popular Beggar’s Opera. Handel had great success here, the Kembles with their battle scenes and spectacles came next, and when the theatre burned down, as they did regularly back then, the Kembles rebuilt it within a year. The first proper season of opera was 1847 and singers brought their own costumes and the Ballet Russes performed here in 1911 and set new artistic standards for dance. The theatre was used for boxing matches and conferences and some wanted to tear it down, but Thomas Beecham had a “thumping profit” in 1937 and after the Second World War the theatre had two resident companies. In the nineties, the Royal Opera House raised 130 million pounds and the theatre, except for the auditorium itself, was expanded in all directions to include the latest in theatrical technology, although no microphones are used for performances. The costumes for the legendary Callas Tosca were used for 40 years and for a production of The Flying Dutchman set in the 1970s, the costume department raided London’s retro shops to find sturdy garments. Today the Royal Opera House has a payroll staff of 950, does 300 performances of 50 different productions over 11 months, and has a 93% attendance rate, so the “books are balanced.” What performers does our guide, Stephen Mead, treasure most in memory.? The Callas Tosca, Begonzi, Christoff who did exactly the same Boris every night, Sutherland’s Lucia, Price, Elizabeth Vaughan who was the greatest Butterfly……I have felt many a frisson in this theatre.

The skeleton of Jeremy Bentham –neck down, at least- sits in his usual chair in a mahogany and glass structure in a hallway of University College just down Gower Street from my B&B. The skeleton is wired together around two vertical supports and, padded with linen, he is dressed as he used to be, with his favorite cane beside him. His real head –the one here is a wax reproduction- is locked away in the school’s safe. Why? For one, the process of preservation had ghastly results, the kind of ghoulish goody one might find on CSI each week, and, second, students of a rival school have tended to steal it. In fact, the head was once discovered in a rail station in Aberdeen. There are displays here and seven different brochures for the taking, all of which explain Bentham’s “greatest happiness for the greatest number” philosophy. These brochures are individually titled with quotes: “religion is an engine invented by corruptionists, at the command of tyrants, for the manufactory of dupes,” “all inequality is a source of evil,” and “the more we are watched, the better we behave.” In the waxen expression of death, Jeremy looks content; maybe death is the greatest happiness.

And here are some various notes made over ten days: Eating as a vegan is much easier nowadays than in the seventies when a branch of Cranks was the only option. VitaOrganic on Wardour Street in Soho offers a dozen hot dishes, a dozen cold dishes, and proof that, in London, if you can’t afford a ticket to a play, you need only open your ears. Over supper, before a play on human relationships, I hear this conversation beside me: “I wanted to meet some guys and I was testing him. So months of buildup and nothing came of it, but he said, ‘It’s still a good story.’ So I said, ‘No, it’s not. Where’s the story?’ He’s already looking at the end of the story before there was a story. He’s rushed to the finish line before reading the book. This is something a lot of scared people do, imagine the ending even when it’s going fine.” Too bad I must rush off to the play, but, almost late for curtain and using a lane between Wardour and Dean Streets as a shortcut, I meet a young woman who asks, “Are you lurking for a gill?” I’m surprised at a suggestion that I have ominous designs on a fish, but she clarifies by stroking the back of my hand and suggesting she give me a massage. “My flat’s right here,” she coos. “My theatre’s down the street,” I coo back, to a dirty look.

Strange that I watched Lang’s Metropolis on the flight over, since Oxford Street is a Langian mass of humanity. The women this year are all Tissot-legged with black stockings or tight black jeans, caps askew over hair that makes a straight silken descent or ripples wild with henna. Most of the men are dressed in uniform functionality. “I buy my clothes in America,” says a lad in the tube. I am in one of the world’s great cultural cities and what I do first is go shopping for underwear and socks, but little else since M&S long ago dipped into trendiness geared to perfect bodies unlike mine. Still, travel means exercise, albeit unexpected. Posh hotels may have gyms where clients can work out, but a B&B simply has no elevator and compels one to climb endless stairs. My room is on the third floor, which in Canada is the fourth, and there is no extra cost for the workout walk. Gower Street is a row of such very pleasant B&Bs –Gower, Jesmond, Ridgemount, Garth, Regency, Cavendish, Arran, Arosfa.

Katie, a Londoner, collecting for a charity on Oxford Street, wants to leave the city because “the people are rude, the government is awful, and the transportation always breaks down.” She doesn’t trust the press and suggests I check out a website called Article 19 because they “tell the truth.” At the NPG, Faye from Liverpool where “they have just one gallery” asks me directions. She has moved to London recently “just so I could visit the galleries” and experience all the culture. “I just love it here,” she says. She says ‘luv’ for ‘love,’ like a Beatle. Inside Selfridges, as the author Cecilia Ahern is signing books and chatting with a long line of eagerly-adoring female reader-fans, a clerk whispers to me that her father, Bertie Ahern, was the Taoiseach (pronounced tea-shock) of the Republic of Ireland and had to resign because of financial irregularities. Cecilia is the author of titles P.S. I Love You, and A Place Called Here. She wears pink, has a turned up nose, parts her long blonde hair on the left side and smiles as each fan has a photo taken, cheek to cheek, with her and then pats her lovingly on the back before leaving. Each one wants to touch the one who touches them.

Haven’t been to Speaker’s Corner of Hyde Park for forty years and the tone of the place is less gentlemanly, less civil, than I remember it. One speaker, full of venom, keeps screaming “Jesus is God” at a Muslim speaker, and another tells a crowd of ten, “They’re lying to you; Islam is devil worship.” Today, at least, hysteria seems the norm. One stand has a sign that advertises www.marxist.com and the “Catholic Information Guild” hoists another sign that reads, “It’s going to get worse.” The place is a mass of chattering and when it starts to rain, the umbrellas come out and the chattering resumes, like a flock of birds in a bush, birds that no one can see. Last visit it was huge variety in British accents and this time it is often British with foreign accents or foreign languages themselves spoken everywhere. But good old British humour still seems ubiquitous and on the tube we hear this announcement: “Sorry, ladies and gentlemen, we are delayed, but it’s better waiting in the station than being stuck in the tunnel. Please do not lean on the person beside you…(pause)….Lean on them only if you know them….(pause)….If you don’t know them, please ask their permission.”

At the Lamb and Flag, with a 6 foot 8 bouncer at the door, it is Jenny who serves me a pint of bitter. I can’t place her accent and she tells me she is originally from Sweden and that she spent 5 of her 10 married years living in the Highlands with her Scottish husband. In the seventeenth century, poet John Dryden was famously beaten up outside these premises and, because of the bareknuckle boxing held upstairs, the place acquired the name “Bucket of Blood.” At the Museum Tavern where Karl Marx drank his brew, I have a pint of Old and Peculiar which makes me feel just that –old and peculiar. Next night, I try the Fitzroy on Charlotte Street, where Dylan Thomas and George Orwell drank, but it’s much too noisy and I slip to a silent pint elsewhere. Outside Waterston’s, once the bookseller Dillon’s, I chat about Kubrick with two devotees who regard the director as a genius. They agree, however, that, genius aside, casting Ryan O’Neil or Tom Cruise in a flick was not inspired.

The well-known Paxton & Whitfield, on pricy Jermyn Street, was established in 1797 and, as one opens the door, it smells as if some of the original cheese is still on the shelves. In less pricey Covent Garden, two very bubbly, very cute young ladies call me over too comment on the synthetic Christmas they have decorated in the window of their shop with the many cosmetic products they sell. I give much praise about their creation, which seems to please. “You should come inside and see our products,” bubbles one but, alas, I need no lipstick. The shop is called Jelly Pong Pong, just in case you, dear reader, do.