My following reviews were published in an alternative paper over the past few years and I can’t help but recommend each splendid CD again. So here we go -unedited, from the originals, so please excuse the occasional bit of information that is no longer relevant. JS.

1) In a year and change, Rodney Crowell will be sixty, and on his new CD, Sex & Gasoline, as before with Fate’s Right Hand of 2003 and The Outsider of 2005, the lyrically versatile and discerningly poetic songwriter again proves himself gutsy, and almost unrelenting in self-revelation, as he explores his worth. Here again he puts his will to truth in the witness box to give testimony against the destructive and wounding BS that sustains too many guys in our patriarchal culture. A male to female confession – “….We momma’s boys have got it in for you/Our faults are many, our virtues nil/We never loved you and we never will”- pulls no punches at showing romantic love as a façade and con job of both the other and oneself. Yet, ironically, what follows is the unforced and delicate shading of regret in Moving Work of Art. In Truth Decay, relationships, even with self-awareness, are tough-going in what seems the quicksand once described by R. D. Laing: “I can’t love you like I want to/If it comes down to what I don’t do….” Girls are taught to “bow your head, lift your skirt…” and, in time, men who think they care or maybe do care can only declare, almost like a character out of Beckett, that “there’s nothing I can do/I’ve done everything I can” and realize a futility in the way “they say true love conquers all/ but they don’t tell you who to call.”

The desperation in Crowell’s wishing “for an hour…to be a woman and feel that phantom power” and in his need to find out “if I’m a decent man/Or if I’m just a joke” is deeply touching. One always senses that Crowell has humanity’s number, be it male or even female, but no matter how deeply he regrets his failings –and no matter how much he hopes a woman might handle and not cause pollution, the Iraqi war, the world’s hungry- the inner world of women remains unreachable, unknowable. So I’m relieved that Crowell doesn’t take an easy route, like some songwriters, and assume that human decency is contingent upon the absence of a penis. But in a world where too many puerile men pass stupidity for masculinity and destroy life and planet in the process, one can only hope there is a solution to be found to our madly competitive and shamefully destructive nature. One can be glad then that Crowell has spoken, as a male “out of touch with my gender,” from his need for truth.

I admire Rodney Crowell on many levels. His instinctively poetic lyrics feel fresh and evocative without his trying to make them so, his music in both melody and style shows variety and an insightful vitality, his production is sonically rich and nuanced even when it rocks, but also the man has a deep need to find out, through his art and his honesty, what the ingredients of his being a man and being a human being might and can turn out to be. At his self-critical best, which shows itself often, he doesn’t pass self-flagellation for honesty, nor does he take the facile way out by removing himself from responsibility in either personal relationships or a rotten social fabric, of which he is part, and simply point at the crimes of others. He tells us what we do, in our lunacy as males, and with courageous integrity reaches for answers one assumes he knows don’t exist. He doesn’t escape into his often consummate art but, instead, faces the blunt fact that, being alive, there is no escape from anything on the planet, especially “the man in the mirror” he described in Fate’s Right Hand who is in some way, in truth, each of us.

2) My favorite CD this month is Shelby Lynne’s Just a Little Lovin’ which on first hearing I found rather low key and now I find addictive. Why? Lynne is one of the best up close singers around, one whose naturally intimate voice suggests that singer and listener are sharing one layer of skin between them. Her emotional shadings, sometimes ethereal and sometimes out and out aching, feel deeply rooted in the fibre of living through relationships, personal need, private joys, and wounds that won’t heal. Lynne’s nuanced voice feels so personal at times that one feels an intruder, but also emotionally bound within the singer’s voice to remain and hear more. For Shelby Lynne, a Grammy-winning singer adept at several genres of music, style ultimately emerges from her private truth and so we believe her.

3) The best CD of the month, by a country (and western) mile, is Say Uncle from the Toronto-based C&W string quintet Lickin’ Good Fried. It’s a collection of top-notch music-making on all counts, especially the intuitive interplay in the band itself, the solidly creative musical chops in the backup, and the loving and witty vocals, of always inspired and clever lyrics, up front. The quintet consists of singer-guitarist (Colonel) Tom Parker, fiddler John Showman, Andrew Collins on mandolin, Sam Petite on bass, and singer-mandolinist Alex Pangman. Pangman, when backed by her very hot Alleycats, happens to be Canada’s premiere chanteuse of traditional jazz vocals.

You’ll find yourself doing repeated listens of Say Uncle’s fifteen cuts. Colonel Tom’s enjoyably distinct lead voice seems a long-brewed hybrid blend of teen crooners like Tommy Sands and Hank Williams, while harmonies or duets with Alex feel true to any musical groove they pick, no pun intended. The musically-compelling and very catchy tunes lock easily into one’s brain and the lyrics cover a range of contemporary and traditional issues without forgoing the latter’s musical roots.

For starters, try the relationship politics of Soap Opera: “You ought to be in the soap opera, each night you switch your act up, rewrite the plot and come up with some new and crazy drama, that’s guaranteed to keep us watching each and every minute of the soap opera.” Who hasn’t known or done that one? But equal pleasures and recognition await in “Your Side of the Bed,” or “Don’t Paint Me with the Same Brush,” or “Leave This Song” with its surreal suggestion, “Do me right and leave this song.” Don’t be surprised if you find this disc sharing listening time with Rose Maddox and her 1940s cohorts and Randy Newman and his witty and ironic post ‘60s singer-writers. Available from www.lickingoodfried.com and soon on itunes.

4) Guitarist Margaret Stowe’s new CD, Mello Jello, is now released and it is a subtly enchanting gem of masterly technique infused with a complex and profoundly gentle humanity. Stowe’s light touch is made of a pinpoint delicacy that feels perfectly conceived and perfectly placed; it feels uncanny with other-worldly nuance; it is beautiful. And, no doubt, to some these thirteen tracks might seem as light as a strand of smoke on a sunny day in, say, 1969. In any case, this is guitar playing of such astonishing lightness and rich delicacy in sound that one pauses in one’s deeper emotions to listen. There is richness of imagination here that takes one through surprising rhythmic shifts, placement of notes, tonal variety that teases one’s imagination, and swing that really does swing. However, as ethereal as this music might be, there is an assertive sense of daring within that improvises with confident purpose. Available from margaretstowe.com or myspace.com/margaretstowe

5) When is the Dalai Lama not the Dalai Lama? Let me explain. Last winter, as the healing person, who had been enthusiastically recommended to me by a friend, was allowing her energies to dance with mine, she played a recording of a deep-voiced individual chanting a mantra. “That sounds like a cross between a Bulgarian bass and a Tibetan monk” said I, remembering my CD of Boris Christoff singing Mussorgsky and an interview I once did with a group of maybe a dozen Tibetan monks. The healing person proceeded to explain that it was supposedly the Dalai Lama doing a mantra he had once chanted to a dying friend, although she had doubts this was true, and she proceeded to give me a copy. I played this recording endlessly, often hours at a time, for several months, and treasured the unique feeling of peace and serenity that ensued.

Enter reality. One day, being an obsessive surfer, I decided to check the veracity of this tale, on the internet, and discovered that this deep resonance of a voice belonged not to the Dalai Lama but to one Hein Braat in The Netherlands. His recording of the Maha Mrityeonjaya Mantra was being recorded and passed around by the multitudes, without recompense to him, all because the Dalai Lama had allegedly said that he would record the mantra, but only if it were not sold but given away freely from one person to the next.

Anyway, the pairing of the Mrityeonjaya Mantra and the Gayatri Mantra are one of several imported CDs of Hein Braat chanting available from www.isabellacatalog.com.I can’t imagine life without mine.

6) Diana Panton’s voice, on the CD If the Moon Turns Green, swings with ease and grace and puts out just enough to seductively draw the listener into her private world. It suggests both ambiguous secrets and understanding good will, and hangs gently like a finely woven gown on a body of partially concealed sensuality, whimsy, longing, vulnerability and purity of trust. Panton thoughtfully caresses each lyric with very slight traces of seductive breathiness, charming slight nasality, and delightful pixiness in a beguiling and very feminine brew. Diana Panton practices an art rarely found nowadays, the art of clean open-hearted delivery with no trace of affectation, mannerism or irony, and I know that somewhere the likes of June Christy, Peggy Lee, Lee Wiley and many others are looking on with approval that here, in our own city no less, we have a special vocalist who means what she sings. And when Diana Panton sings in her distinctive lights-are-low, whisper-in-your-ear voice, the world is a good, romantic place to be. Give her a listen and smell the roses. Available at www.dianapanton.com .

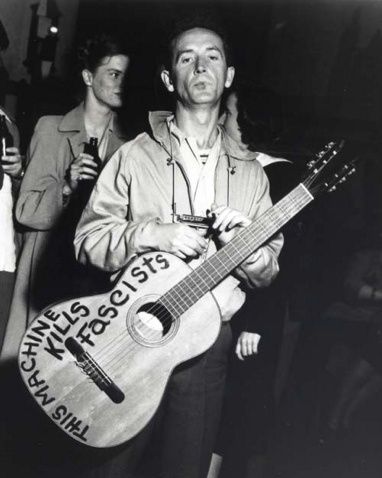

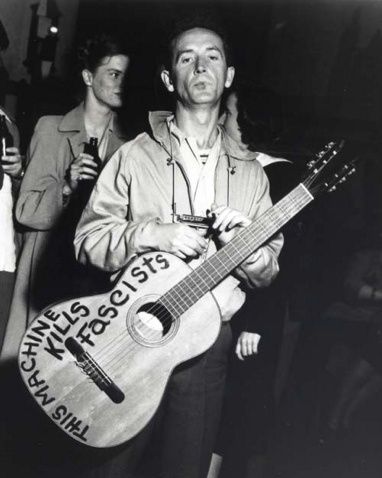

7) I met Ramblin’ Jack Elliot the first time in 1962 at a folk club in Hamilton called The Happy Medium. He was a disciple of the folk legend Woody Guthrie who once had said, “Jack sounds more like me than I do.” Another Guthrie disciple was Bob Dylan, who had recently dropped into the Medium, without playing, and whose first LP had featured a track called Song to Woody. Dylan, it turned out, was borrowing some of Ramblin’ Jack’s Guthrie-derived stage act, although the latter’s brilliance as a raconteur, flat picker (Ian Tyson has said he long wanted to flat pick as well as Ramblin’ Jack), and genuine folkloric persona was and is beyond emulation; for the guy was and is unique. Anyway, when I asked Ramblin’ Jack to tell me about Woody Guthrie, he politely drawled, “Well, you see, my woman’s just in from Toronto……” and the case was closed, at least until we met again.

Memories aside, the release of THE LIVE WIRE: Woody Guthrie in Performance 1949 is a major event for so many reasons. Guthrie’s impact on both folk music and popular music -as a source of classic songs like This Land is Your Land, as an icon of the feisty everyman troubadour speaking eloquently for the working classes, as a major template-setting influence on Dylan, Pete Seeger, Billy Bragg, Ramblin’ Jack, son Arlo, and countless others- has been enormous. But other than brief footage of Guthrie singing John Henry with Brownie and Sonny, who could tell further what this small-framed national treasure sounded like in front of an audience, what his irresistible magic might be. Thus, this CD, available exclusively from www.woodyguthrie.org is a recording of major historic importance because it documents the voice of unions, of migrant workers, of miners, of the downtrodden everywhere and of the American land –and that voice is Woody Guthrie just being himself.

THE LIVE WIRE: Woody Guthrie in Performance 1949, the 2008 Grammy winner for best historical album and a fundraiser for the Woody Guthrie Foundation, took place at the YM-YWHA’s Fuld Hall in Newark, New Jersey and consists of “18 tracks of songs, stories and conversation.” The songs include Tom Joad, Guthrie’s condensation in song of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, Pastures of Plenty with its spine-shivering line, “We come with the dust and we go with the wind,” and Jesus Christ, set to the folk tune Jesse James. For the latter song, wife Marjorie notes that Woody, after being torpedoed , came home with a long beard and wearing a fez, which caused neighbourhood kids to yell “Jesus Christ has come!” Marjorie, acting as hostess of the gig, adds that Woody “lives the life of Jesus Christ very much in his travelling.”

Along with Marjorie’s endearing giggle and attempts to control Woody’s rambling tales with warnings like “I’m gonna time you” and “very briefly this time please,” we have her explanation (quoting Woody) that “folksingers don’t have voices, it is the words that are so terribly important.” From the man himself, unbending individual that he is, we have elasticity of tempo, a false start too high for 1913 Massacre “about the scabs and thugs,” some biographical background (my mother was “an awful scared nervous kind of woman”), historical background about Woody’s home state Oklahoma where the Indians and poor Negroes were cheated out of their land and its oil, and insight into his creative process with Marjorie noting that Woody keeps clippings “stuck up on the wall” and writes up to ten songs a day. I especially love the folksy wisdom of “Oklahoma’s first in everything worst” and Guthrie’s famous ironic wordplay with “since I was there and the dust was there I thought I’d write a little song about it.” We are so damned lucky to have this priceless recording available.

8) In the exquisitely designed booklet of her musically abundant and aesthetically seductive new CD, Kulak Misafiri: Events in Small Chambers, singer Brenna MacCrimmon offers seven definitions, of the title, that suggest we inhabit and are remade by a lifelong continuum of sound that works its magic upon us, through us. MacCrimmon’s magical contribution to the listener’s aural life is a collection of eleven (of thirteen) tracks that are subtly potent and undeniable with syncopation, juicy-ripe with musical textures, vocally haunting, mysterious in aura, and solid yet spontaneous in musical sophistication. Canadian MacCrimmon certainly conveys a love and reverence for this blend of mainly traditional and several modern songs, but so brewed is she in the complex idioms of Turkish music that one senses the roots of her spirit are planted in the blood of Turkish soil. Recorded in seven cities with small groupings from a pool of thirty-one ace musicians, the riches here are many and each track seems an event in its unique way. Gems include Dolama Dolamayi with its punctuated lilt and descending refrain, the jazzy underpinning of Oj Ti Mome Ohrigance, the heart-broken and blood-bleeding wail of Yildiz Dagi with George Chittenden doing eerie turns on the zurna, and the deeply blue Semsiyemin Ucu Kare for which MacCrimmon explains “There are days when the rain and the mud and the clouds get into your soul.” Tracks eleven to thirteen include birds singing, MacCrimmon singing the self-penned, loving and soothing Mussels in the Bay, in English, that suggests the kind of drifting smoke one imagines to find in Istanbul, and, finally, what sounds like the interior of a train station somewhere (a continuum of sound, remember?) MacCrimmon’s distinctly pure voice, one that is crystalline yet fleshy, timbred when needed with an edge of nasality that is de rigueur when one moves east from the music of western Europe, is, like this CD, one of a kind. Kulak Misafiri: Events in Small Chambers certainly has many qualities to make it a special classic of contemporary world music -and holding graphic designer Yesim Tosuner’s beautiful booklet in one’s hand is a bonus. A must have, to be sure. Available from www.greengoatmusic.ca or www.cdbaby.com/brennamaccrimmon

9) On I Love (Heart) Jokes: Paula Tells Them in Maine, the quick and kind comedienne, Paula Poundstone, is brilliant at connection with her audience members. She points out and probes the absurdities of their lives and ways of speech, all with a benign aggressiveness that does not patronize or condescend or abuse, but lovingly celebrates the average guy or gal. She is a mirror that, without judgment, says “look at yourself, laugh and enjoy.” Poundstone makes the folks in her audience talk and, whatever each one says, she picks up on the potential of every sentence -or silence- and takes their words -or lack of words- at face value and riffs on them. She does so with a snow ranger, a woman who “runs a national park,” and a professor of statistics, and each exchange is hilarious. She also applies her modus operandi of wide-eyed amazement and awe to Maine and its people, parenting, aging with its wrinkles and poorer vision and jowls, cats (she has 12) for whom she sifts “all day long,” and tosses in that “Canadians are the nicest people in the world” -with a caveat about our reticence to speak up for ourselves also tossed in. Poundstone is special and already I’m playing her CD a third time, as you will too. But be careful while driving: this CD is pee your pants funny. Go to www.paulapoundstone.com to order.

10) Here’s a take on Richard Thompson, using the five CD set RT: The Life and Music of Richard Thompson (on Free Reed Music) as reason and evidence. As a lyricist, he is unflinching yet compassionate, incisively aware of a world where people live impossible realities, always surprising in his turns with colloquial language, deliciously acidic in his irony, achingly poignant without even scratching sentiment, and funny as hell (a song on Janet Jackson, folks, and Madonna too). He is good because he rarely points at others in accusation, unless they are ridiculous, or at himself in congratulation for his versatile genius.

As a guitarist, Thompson shapes each riff as if it’s conceived for this very moment alone, while sonically he incorporates a range of sounds from the nuances of Celtic music, especially the pipes, to rock of all styles from Chuck Berry to The Who, to pure sound of shifting tonal base into a unique experience that, for all its musical savvy, emanates whole from a creative centre and not as an amalgam. As a picker, he is versatile, imaginative, and no slave to any stylistic form as he creates his own distinctive sound. His sense of sonic space is gripping, his musical imagination unending, his technique masterful.

As a singer, Thompson can do an everyday bloke or a wandering everyman in purgatorial solitude or a George Formby clone with a macabre edge or a human spirit surveying a bottomless personal chasm or a knife poking commentator full of phlegm. His individual cuts are memorable as complete creative entities where all his masteries meld. Just the unreleased recordings in this collection would make a distinguished career. Available at Records on Wheels in Dundas.

11) In his Pensees of 1670, Pascal stressed the underpinning of human essence in the arts, saying, “When we see a natural style, we are quite surprised and delighted, for we expected to see an author and we find a man.”

Where the creative person matters most deeply, to be sure, is not in doing art for the sake of doing art, or for profit, or for, say, Canadian Idol status, although the latter is a nice gig for the perks, prestige and bucks. The creative person matters most in manifesting and sharing his or her genuine individuality and profound concerns through mastery of a given art form.

Yes, it is hard to reveal, and sometimes to accept, one’s own uniqueness in our “more of the same” culture. Moreover, even offbeat artists can become cliched if all they seek is to achieve difference from the norm. But as film director Terry Gilliam once told me: “It’s our duty to do something, if we’ve got skills or talents, to help improve things.” By being real, the genuine artist can initiate real change in the world itself or how we experience the world, and both changes are essential to our worth as humans.

That’s why it is always encouraging to witness a major talent plugging away, in a given creation, for both truth and consummate artistry at the same time.

In classical music, for example, Magdalena Kozena’s recent Mozart Arias on the Archive label, with offstage mate Simon Rattle conducting, reveals the Czech mezzo’s vulnerable, yet uncompromising, sincerity that consistently aches with the beauty of human risk and of universal truth. Or in country music, Rodney Crowell’s Fate’s Right Hand pulsates with unrelenting introspection and existential guts that compel the singer-songwriter to find and know himself. Or Mexican Chavela Vargas whom the singer Lhasa once made me promise to check out for her unflinching honesty. Vargas turned out to be intensely real and unforgettable.

But not all art, to be true, needs to be angst and pain. Joy is equally honest and real, although many performers in our age of perpetual smiles seem unable to realize their own profound inner buzz without resorting to façade or gimmickry of some kind. That’s why nowadays, when I find many new and “smooth” jazz singers as stimulating as Prozac, I turn to Alex Pangman for life and music as one inseparable high. Alex is a quintessential upper, an unaffectedly hip singer with style in her blood who lives and breathes the swing idiom.