JAMES STRECKER: You are known, among other reasons, for your interest in the meditative and restorative power of music, so I wonder how this interest is in evidence in your new work OM SAHA NĀVAVATU.

TIMOTHY CORLIS: The words “OM SAHA NĀVAVATU” are the first three Sanskrit words in a mantra that is often used in meditation. I personally use this mantra in my own daily meditations as a way to invoke peace in the moment. It’s a popular mantra or prayer for meditation and many others have adapted and set this mantra to music, including pop singer Tina Turner. It translates loosely, “Aum, May we all be protected, May we all be blessed, may our interactions and affairs be filled with enthusiasm and energy, may the things we learn be filled with brilliance and light, may there be no conflict among us, Aum, peace, peace, peace.” When I sing this during meditation, there is no audience, just me. I sing it as a prayer, but also because it allows me to concentrate, to put aside the constant noise of daily life, and the constant monologue that my mind creates from moment to moment. When I can do this, with this mantra and also with other similar short devotional songs that are helpful for focusing one’s concentration, I’m able to find a part of myself that leads to my own restoration. This is the simple power of music to act like nourishment, like “soul food” that helps us feel rejuvenated inwardly each day.

In our daily lives, we are often bombarded by noise, we are constantly taking in new information and responding to rapid stimuli. This is necessary to survive in the modern world. Beyond that, even when we have the time to decompress and relax, our minds continue to generate a monologue… what will I have for dinner, I like eating baby spinach because it’s nutritious, what time does the bus leave in the morning, where are my glasses, I should buy new running shoes, etc. It’s very difficult to experience even a few moments of real silence, yet we know that silence is very good for us and this is where mantra in music can be very helpful, because it prepares us for a moment of peace, when we can be fully engaged with the silence.

JS: Please tell us what you want the public to know about your new composition. For instance, what exactly is it and why did it come to exist?

TC: I’ve often heard people who attend concerts or people who sing in choirs, especially for classical concerts, describe how therapeutic the experience can be. I’ve even heard conductors joke sometimes, “Why sign up for therapy if you can sing in a choir!” There is also research that shows that singing music increases our mental and physical health, not in an abstract way but with clear physical indicators that immune responses are more robust and stress indicators are reduced after people experience music together.

But, this goal of creating therapeutic experiences through music is rarely something that we talk about as being at the forefront of concert music creation. As composers, we often talk about the techniques of harmony and rhythm, we talk about writing idiomatically for instrumentalists, we talk about impressing an audience with exciting innovations or ideas, or we talk about authentic self-expression. All of these are important and valid aspects of the process, but for this work I wanted to focus on the personal therapy side of music. I wanted to create an experience in the concert hall that shares the kind of personal “soul food” that refuels me when I meditate in silence on my own, when I sing simple mantras as a way to invoke inner silence.

Because of this slightly different goal, OM SAHA NĀVAVATU is more of a sonic experience than a concert piece. Lydia Adams, director of the Elmer Iseler Singers and I call it a “sound journey,” meaning that some aspects are like traditional choral music with melody and harmony, with beautiful poetry set to music, and other parts are purely like bathing in sound, allowing gentle textures of sound to flow through the concert hall as a way to access a feeling of inner peace and silence, to just feel bliss and tranquility in the moment.

JS: Please give us a brief autobiography, some stuff about yourself that is relevant to this composition.

TC: When I was a young adult, I had an opportunity to spend some time in India, at the Institute of Gandhian Studies, an ashram in Wardha dedicated to the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. I remember we rose early each morning and gathered to sing the favourite Vedic Hymns of Gandhi. This was probably my first experience with mantra-based meditation as a daily practice. That was in 1994. I had grown up singing in an Anglican boys’ choir at school and attending church with my parents at Bloor St. United Church, Toronto. I was struck by the differences between the experience of singing the music of Gabriel Fauré, Benjamin Britten, Palestrina, Bruckner, or Mozart in the cathedral and the experience of singing Vedic hymns at the ashram, one relatively complex with a lot of preparation, and the other relatively simple and repetitive. I came to love both.

Over the years, these formative experiences, both the experience of studying in India and the experiences of my church upbringing stayed with me. Eventually, I developed my own personal meditation practice, with an openness to the many different ways that one can approach meditation and prayer. In Western contexts, we can enrich our lives tremendously if we are open to different ways of experiencing music through other cultures.

For OM SAHA NĀVAVATU, I wanted to bring two worlds together and try to create a genuine concert-hall version of the way I’ve experienced music for many years, through mantra and meditation.

JS: In what ways was this composition fairly easy to do and in what ways was it difficult to realize? How long did it take and why that long?

TC: The early stages of writing this work happened in the midst of the pandemic when live music was all on hold. Like many others in the arts, I watched one date after another disappear from the calendar, one concert or commission after another cancelled. This is particularly demoralizing when you see conductors who have taken on your major works for international premieres, in New Zealand or France for example, have to cancel their engagements. Well into the second year of the COVID freeze, I began to wonder if this would continue indefinitely. I wondered if perhaps one new strain of the virus after another would emerge and keep us all in this unprecedented state where no live music, in the entire world, was ever performed. At the time, it certainly seemed like this was a likely future.

This was all very depressing and dismal for those of us who work in the live-concert space, but there was a profound upside. For me, my focus had to shift, my raison d’être had to change. And so, I started writing music for my own personal emotional health. I began spending time each day simply writing without any expectation for a live audience or for a performance, without anyone to impress, also without any paycheque or commission. I began to write simply because I wrote… and so it’s not surprising that the music began to resemble more and more my own meditation practice. I found that more and more I became immersed in playing the music, and simply enjoying the experience of the beautiful sounds on the piano, as if I were singing simple mantras during meditation.

Once the restrictions of the pandemic did eventually start to subside and it looked like there were going to be live concerts again, I approached Lydia Adams, Artistic Director of the Elmer Iseler Singers, with the idea of a piece of music with the goal of creating a therapeutic experience in the concert hall, a work that would deliberately engage with music as a meditation experience. Both she and Jessie Iseler, the choir’s General Manager, immediately understood what I was trying to achieve and embraced the project wholeheartedly. The singers in the choir also have enthusiastically engaged with the philosophy behind the work and with the sound healing instruments that we are using to create a mood of calm and tranquility. It’s been a long time coming, but finally after 3 years, on October 22, 4pm at Eglinton St. George’s United Church in Toronto, the work will receive its premiere performance as part of Elmer Iseler Singers’ series concert “Walk and Touch Peace.”

JS: How did doing this composition change you as a person – and as a creator?

TC: The Nobel Prize winning Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore sometimes shared a story about the teacher and the student. The teacher attempts to explain to a frustrated student… The performer who sings for an audience, sings music that is meant for an audience. The performer who sings for God sings music that is meant for God.

Some of the music of J.S. Bach that I most admire is the music from near the end of his life, the Goldberg Variations, the Art of Fugue, the Mass in B Minor. We know that Bach wrote much of this music without any real prospects for performance. Perhaps this was all for posterity, but I feel that by then, perhaps he was writing in the way that Tagore describes. By the time J.S. Bach was an old man, his music had long gone out of fashion and had been eclipsed in the public eye by flashier classical composers. Complex preludes and fugues were passé. Yet, Bach still wrote volume after volume. Also Fauré, in writing the Requiem expressed relatively little interest in the performance outcome. He was not commissioned, but instead simply wrote the piece for his own benefit, for enjoyment or to increase his own happiness. In his own words, “My requiem wasn’t written for anything – for pleasure, if I may call it that.”

For this work, OM SAHA NĀVAVATU, both through circumstance and also as a choice, I wanted to find out what it would be like to write like this, day after day. To write simply in the moment, to invoke the divine, for myself as I touch the piano, or sing as a way to delve more deeply into my own heart, as a way to heal my own accumulated pain from old emotional wounds, whether self-inflicted or inflicted by others, and as a way to search for a higher, more compassionate version of myself.

JS: What kind of audience will this project interest? What new audience are you also seeking? Why to both questions?

TC: I hope that this project will help people who have suffered as a result of the pandemic. Many of us have lost loved ones to the virus, some have lost their livelihoods as businesses collapsed or as the changing landscape of the pandemic chose economic winners and losers. An entire generation of young adults have had the most important years of their lives lobotomized, all the joy and fun of high-school and university, meeting new friends, in-person, having the time of your life as a young person, replaced by a stream of text messages or social media posts on Instagram or TikTok. Young people have shown extraordinary resilience finding creative ways to interact online. Still, by comparison, such a lonely, lonely experience. And many who are elderly, were quarantined in loveless institutional prisons month after month, many had no idea why their children never visited, and passed away without their families around them, wondering why they were abandoned.

One of the poems I set… for the last movement of the work, is a poem called “Hope.” The poem was written by a man, who I consider to be one of the great lights of the twentieth century, Sri Chinmoy. The poet depicts a conversation between a personification of “Hope” and a sincere seeker of the divine, “Hope, my most precious friend… my most dependable friend. Only because of you, can I live on earth… Only because of you, do I dare to believe that one day the divine in humankind [sic] will be fulfilled.”

I feel that this word “Hope” is of tremendous importance to those who have been marginalized by the pandemic, the elderly or those who have fragile health. I also feel that this word “Hope” is perhaps the most important word for people who are emerging adults right now. Amongst this generation, I feel a tremendous hunger for a better world, a more self-aware world. This possibly, is how the pandemic functioned as a push towards something more: hope… that is, hope for openness to difference, hope for acceptance, hope for love and meaningful friendship, hope for a sustainable relationship with the planet. I also hope that all the suffering that the pandemic brought about, all the loneliness and despair it created will inspire young people to find something deeper within themselves and to steer us all in a new direction.

So, to answer your question about who this work is for, OM SAHA NĀVAVATU is a mediation sound journey that I created for those who struggled most with the pandemic, for the elderly, and for a generation of emerging adults, all who have struggled with despair through the past few years.

JS: What might others not understand or appreciate about your composition?

TC: Given that the purpose of the work is to create inner calm and meditative silence, probably it’s best to approach the experience of hearing it with this in mind. I find often when I listen to the music of John Taverner, Arvo Pärt, or Henryk Górecki, there is a moment where I have to decide whether I’m going to be bored or engaged. Usually after the first, say, 15 minutes of Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa or Górecki’s Symphony #3, there is a moment where my mind gets tired of the repetition and that triggers boredom. That’s often the point, depending on whether I’m in the right space, that the music engages something deeper. The ramblings of the mind clear away like fog, and what emerges directly in front of me is the light within my own heart.

One does not have to practice meditation, be a Buddhist or a Hindu to understand this. People who participate in the Christian church tradition understand this opening of the heart through mantra in music, especially in more Eastern Orthodox contexts, also in the tradition of Gregorian Chant practiced in monasteries around the world, or in the Taizé tradition in France. This sort of experience in music requires some patience. It’s perhaps not for everyone or for every day. But, when we are open to these experiences, then it can be very nourishing and renewing. When we engage in this kind of activity regularly, it can also be healing emotionally.

JS: What are the most important parts of yourself that you put into your work?

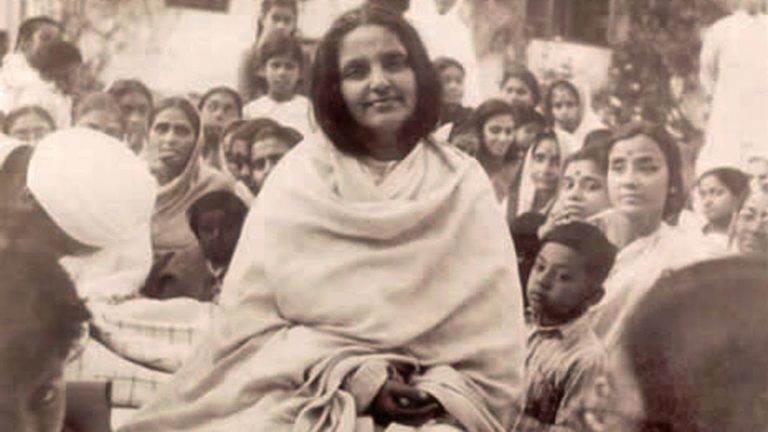

TC: One of the other poets that I set to music in this work is Anandamayi Ma. She was unusual because she was one of the few female Spiritual Leaders who lived in India, mid-twentieth century. Her name “Ananda” means joy and “Ma” mother. When you look at photographs of her face, you immediately feel the immense inner calm. There is one photo in particular where you see this most clearly, where crowds of people are bustling around her with anxiety in their expressions and she sits, looking directly into the camera with absolute poise.

As a composer, I can relate to this photo. I look at her capacity for calm amidst chaos and wish that I had that level of poise. For 20 years of my time as a professional composer, I remember spending a lot of time in noisy urban contexts desperately trying to find a quiet place to work! For the past few years, I have been fortunate to live and work in the Gulf Islands in British Columbia where there is a lot of silence, and a lot of opportunities to meditate in that silence.

The poetry of Anandamayi Ma, “…by the flood of your tears, the inner and outer have fused into one… you shall find her whom you sought… nearer than the nearest, the very breath of life, the core of every heart.” While writing the music for this work, I often felt inspired by silence, the peace that one feels in a place like the Gulf Islands, or a glimpse of the inner silence inhabited by people like Anandamayi Ma, this is what I hope others can take away, even a just a taste of this silence-experience, from listening to OM SAHA NĀVAVATU.

JS: What are your biggest challenges as a creative person?

TC: I suppose the biggest challenges that I face as a creative person are similar to the challenges that we all face. We are confronted with a trajectory, driven by economic growth and population growth, that is obviously not going to last. Our impact on the environment that supports us is staggeringly destructive and even as the scientific community sends out one red flag after another, we still run head-long towards the same unsustainable result. I see this in living colour every day in the Gulf Islands, where wildlife is abundant. Our house and the studio where I write is a place surrounded by a thriving ecosystem, where we frequently see eagles, hawks, ravens, deer, owls, otters, seals, sea lions, dolphins and whales of all types. At the same time, every single day we watch 3-4 oil tankers or container vessels travelling the shipping lanes and dwarfing the whales that swim alongside. The juxtaposition is a constant reminder that the abundant beauty surrounding us is fragile and doesn’t stand a chance in the face of the astonishing might wielded by industrial interests. It could be gone at any time, as it has disappeared in so many other places around the world.

The Buddhist poet Thích Nhất Hạnh, another great spiritual leader, who I have the privilege to set to music as part of this Sound Journey, writes, “Walk and touch peace at every moment, walk and touch happiness at every moment. Each step makes a flower bloom under our feet. Kiss the Earth with your feet. Print on Earth your love and happiness.” As a creative person, and as a spiritual person, I feel the greatest challenge of all is living into a life like this. We are all part of the problem and the solution, we still heat our house with fossil fuels and drive gasoline vehicles, we still travel by jets that leave a trail of CO2 behind them, we still create waste that pollutes the oceans and that ends up in landfills, yet at the same time we hope to live into a life where love for self and others, and love for the earth, blossoms with each step.

JS: Please tell us what you haven’t attempted as yet that you would like to do in the arts

TC: When I listen to recordings of great spiritual teachers singing music, or playing music, recordings of Sri Chinmoy or Srila Prabhupada, or when I read the poetry of Anandamayi Ma or Thích Nhất Hạnh, what comes across is not virtuosic skill or technical perfection. What comes across is sincerity, that and a total disregard for the judgements of the audience. There is also a kind of curiosity, a childlike eternal beginner, free of ego and anxiety.

Like many performers, I have often struggled with nerves before and during performances. Sometimes these would get in the way of performing accurately and other times not. When I started meditating before performances, I found that at certain concerts, this problem almost completely went away. Not all the time, and not entirely, but it helped a great deal and minimized the impact of anxiety on my ability to perform. This is one goal I would eventually like to reach with my writing as well, a fearless place where the eternal beginner in me can thrive.

I feel that this type of fearless child-like creation is close to what Rabindranath Tagore referred to in his story about the teacher and student. In this creative place, the heart can open like a flower, not in a sentimental or gushing way but in a way that leads to deeper compassion and inner tranquility. OM SAHA NĀVAVATU is my first attempt at this way being an artist…it’s an “eternal beginner’s” beginning, and I’m hoping what will follow, is a long process of spiritual growth and emotional healing through music, both for myself and for those I work with.

SPECIAL NOTE: This commission and performance of Om Saha Nāvavatu are funded by the Canada Council for the Arts.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5508386-1598299329-8598.jpeg.jpg)

![Angela Hewitt - Scarlatti: Sonatas, Vol.2 [New CD] - Picture 1 of 1](https://i.ebayimg.com/images/g/tUIAAOSwWflZ-7dj/s-l500.jpg)

Photo by by Alexander Kurov

Photo by by Alexander Kurov Photo by by Todd Macdonald

Photo by by Todd Macdonald Photo by by Todd Macdonald

Photo by by Todd Macdonald